P3 7-8/2022 en

What Does it Mean ...

Education Gap

This issue of the educational gap is about the Portable Document Format (PDF). However, behind the Adobe long-running favorite, which is a daily companion for most of us, there is a multitude of details that can have a direct effect on the application and use of PDF files - especially in prepress. Ronald Weidel from the Gutenberg School in Leipzig gives an overview of the format and the various standards that are based on it.

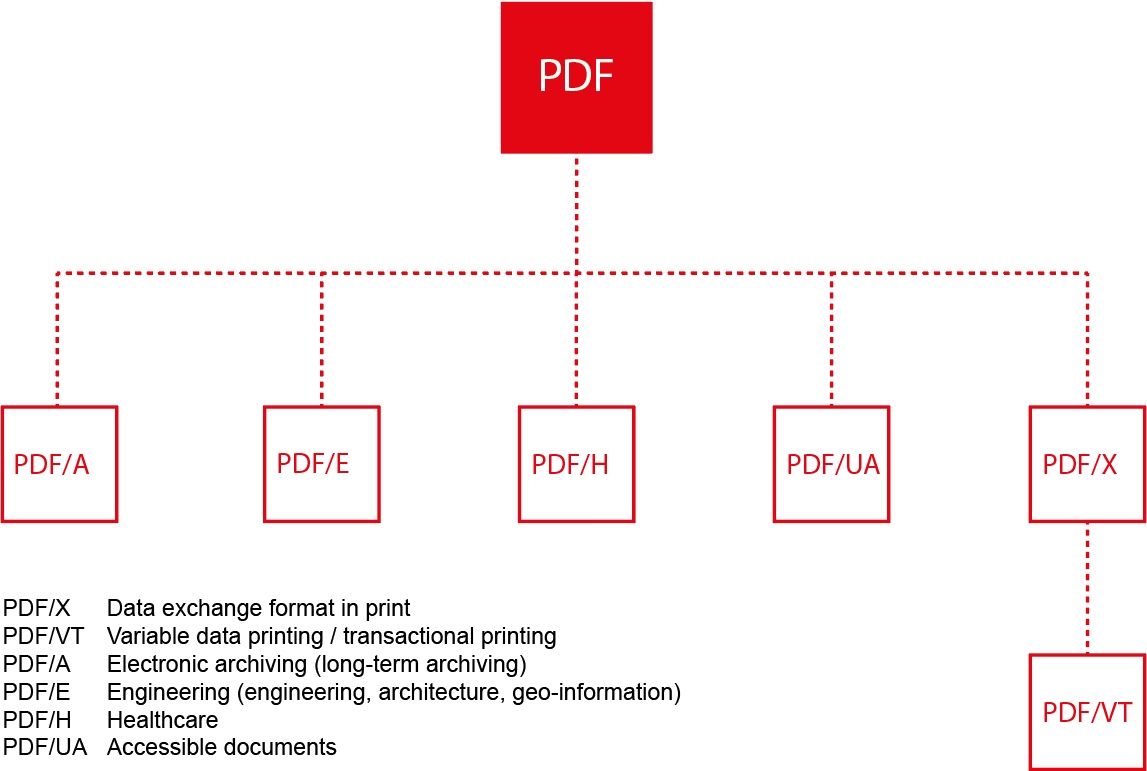

Fig. 1: The PDF family.

We use it every day: for invoices, operating instructions, tickets or as a digital form. When it comes to exchanging documents, PDF is the first choice. Modern prepress would be unthinkable without PDF. The time-consuming and sometimes adventurous data transfers from the early days of desktop publishing are long history. The PDF family has grown significantly over the years, so that a large number of versions and subsets are used today. Even professionals can find it difficult to overlook the variety. It's a good idea to take a look at the status of developments and discover new functions from time to time.

The Portable Document Format (PDF) was originally developed by Adobe and published in version 1.0 in 1993. The developers working with John Warnock wanted to create a data format that would allow documents to be passed on and output electronically without changing the appearance specified by the author. Application-related line and page breaks or changing the font should be avoided. Right from the start, the focus was on the independence of applications and platforms. A specially provided software (e.g. Acrobat Reader) should enable reading and output on different operating systems. The overwhelming success of the format finally prompted Adobe in 2007 to bring PDF technology into the standardization process of the ISO (International Organization for Standardization). On July 1, 2008, PDF version 1.7 was converted into an open standard and included in the standardization work under ISO 32000-1:2008.

Even before the start of the standardization process, subsets of PDF developed that were specially tailored for specific areas of application. This includes, for example, PDF/X for the exchange of print data or PDF/A for the long-term archiving of electronic documents. Many other applications have since been added. Figure 1 shows the current PDF family.

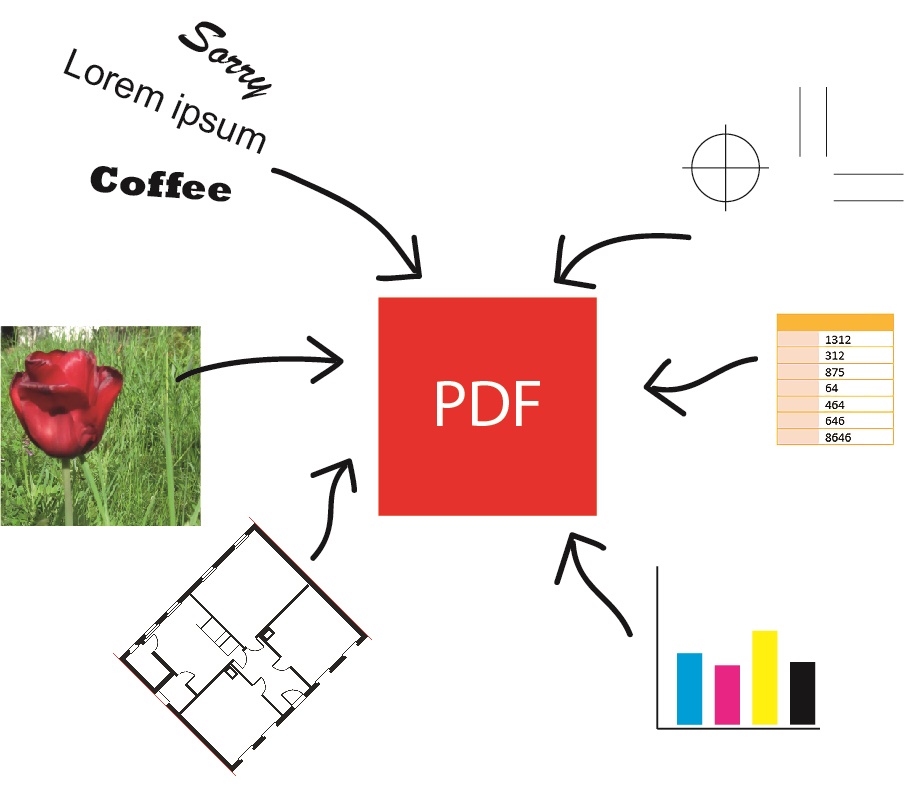

In the following, special attention will be paid to PDF/X. In this case, X stands for Exchange. The basic idea for PDF was simple: the format should be able to contain all the typical resources of a document. This includes text, pixel and vector data, fonts and other tools such as navigation elements or color information. This makes PDF ideal for data exchange in the printing industry. The format caught on at the latest with the introduction of the direct export function in the relevant DTP programs. PDF is often only referred to as a data format, but it really is a full page description language that takes many concepts from Postscript. One of its essential properties is the vector-based storage, which enables a scalable output of the content with only a small memory requirement.

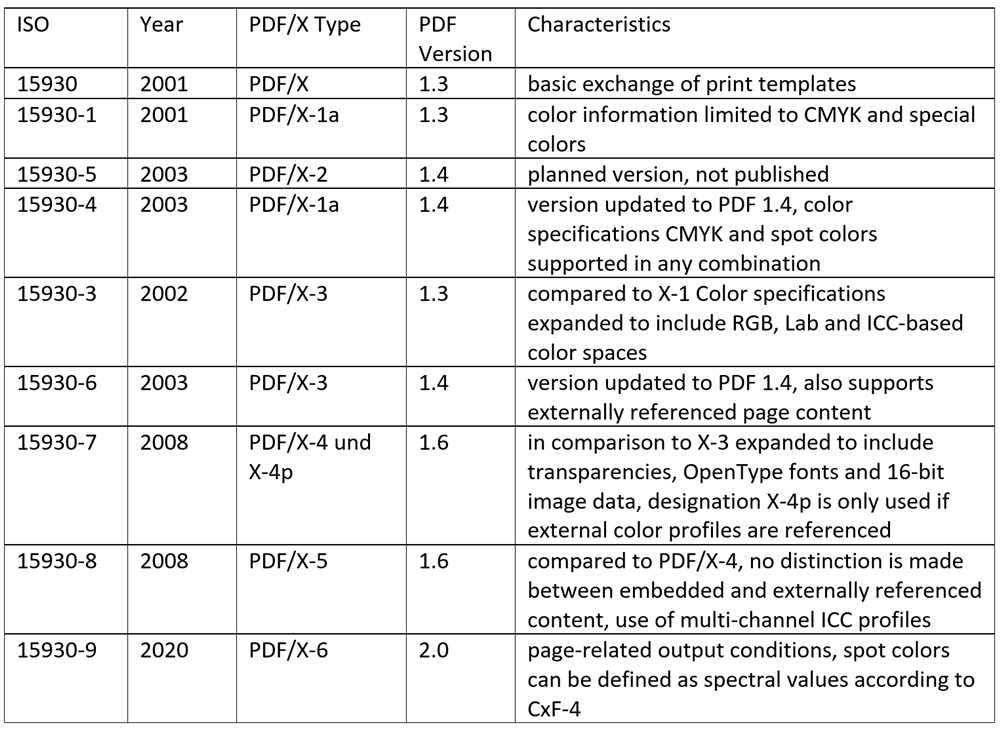

Various PDF/X formats have emerged over the years, each of which represents a minimum requirement. The focus is on the properties of a printable document, so features such as hyperlinks, video and audio content, for example, are not allowed. Each PDF/X standard originates from an underlying PDF version and is classified in the ISO standard series 15930 ff. Table 1 gives an overview of the existing PDF/X formats.

Another important data format is PDF/VT. It is a derivative of the PDF/X-4 and PDF/X-5 format for variable data printing (also known as VDP = Variable Data Printing) and transaction printing. PDF/VT is used, for example, in digital printing - for the personalized printing of individual elements or entire page content. A ready-made template is combined with variable content such as addresses, personal text blocks or image content from a database. Using PDF/VT, database-driven content printing is expanded to include valuable color management functions. While variable data printing is often used for targeted marketing campaigns, transactional printing is typically concerned with the production of insurance policies, bank statements or utility bills.

In the end, the question arises: Which version of PDF/X should be used in the printing process? PDF/X-1a, PDF/X-3 or maybe PDF/X-4? There is no right or wrong here. The PDF/X standards build on each other. With each version, functional scopes have been expanded and new requirements taken into account. A new standard does not replace an old one. Coexistence is expressly desired. Rather, a correctly created PDF/X-1a would also meet the conditions of a PDF/X-3, but does not fully exploit its technical possibilities such as extended color definitions. Many print shops have been using the PDF/X-3 standard for years because it covers the essential requirements.

However, PDF/X-4 is more flexible. The possibility of integrating transparencies allows a more in-depth correction of the elements in the exported PDF/X-4 format. Up to the PDF/X-3 version, transparency had to be reduced when exporting. To do this, areas with transparency are broken down into individual image areas and converted, fonts are partially converted into paths, and the selected color space is tightened. Corrections to the PDF are no longer possible in these areas, and the full-text search no longer recognizes text that has been converted into paths. The use of PDF/X-4 expands the possibilities, but it must also be noted that not every RIP interprets PDF/X-4 properly. Transparencies are known to provoke unwanted effects in the RIP. Missing frames, broken gradients, or black blocks are common mistakes. Before making the switch, sufficiently reliable tests should be carried out with the RIP. If unwanted effects occur, you should initially stick with PDF/X-3. A switch is then only recommended with a new RIP based on the Adobe PDF Print Engine (APPE).

Author and Dipl.-Ing. Printing Technology (FH) Ronald Weidel has been working at the Gutenberg School in Leipzig as a teacher for printing technology since 2008.

Author: Ronald Weidel

Editor: sbr

Images: Ronald Weidel